Five Changes Great Leaders Make to Develop an Improvement Culture

Optimizing leadership skills is more important than ever, given a fast-changing health care environment rife with competitive new services such as CVS MinuteClinics, virtual second-opinion specialty shops, and offshore 24-hour radiology reading services. To adapt, and survive, organizations must take advantage of every bit of institutional talent. But this can happen only if leaders first embrace the need to change.

The qualities of willingness, humility, curiosity, perseverance, and self-discipline have long been leveraged by innovative industries worldwide, yet the health care industry has been slow to catch up.”

But in what ways should a leader change? Many books and scholarly articles describe strategies for leadership improvement. For example, the Lominger Group identified more than 30 key behavioral traits required for outstanding leadership, including “political savvy” and “dealing with ambiguity.” At Catalysis, we have distilled important leadership qualities down to five key behavioral dimensions that, together, are essential for fostering a culture of continuous improvement: willingness, humility, curiosity, perseverance, and self-discipline.

Our work with health care leaders has shown us that cultivating these five areas can help improve health system performance. Institutions seeing positive results include St. Mary’s General Hospital in Kitchener, Ontario; UMass Memorial Health Care in Worcester; and Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, for which we will present a case study. But first we present our ongoing work with health care leaders.

The Making Of A Continuous Improvement Leader

In 2014, Catalysis invited 40 health care CEOs from across North America to participate in a CEO summit. We organized the leaders into two manageable cohorts, each of which uses a common set of principles and encourages behaviors that build long-term sustainable management systems. Leaders meet twice yearly for half-day learning sessions on such topics as establishing leader standards for supporting frontline workers and developing strategies for understanding customer needs.

The groups achieve common learning objectives through activities based on principles for developing operational excellence. However, the most powerful learning occurs when peers work together, sharing candid stories about personal behavioral change. This open environment of trust allows executives to build strong relationships, including a “buddy” system for tackling topics impossible to discuss within one’s organization.

Becoming a continuous improvement leader takes coaching and plenty of practice. Participants become better leaders by ‘acting their way into thinking.’

Becoming a continuous improvement leader takes coaching and plenty of practice. Participants become better leaders by “acting their way into thinking,” and our faculty designs opportunities for practice. For example, participants might work together in groups of three on a real-world problem they are facing at their organizations. One person observes, one asks questions, and one answers questions. The learning power comes from the feedback each receives from their peers. Everyone rotates through the three stations to experience each role.

Participants are also coached on actively listening and asking effective, open-ended questions, the latter a reinforcing behavior important to successful cultural change. Back home, they are encouraged to enlist others to observe their daily interactions. Above all, they continuously build on their learning and dare to experiment.

During the course of working with our CEOs, we found that the five important behavioral dimensions we have identified consistently underlie the changes leaders must make.

What Other Industries Can Teach Us

The qualities of willingness, humility, curiosity, perseverance, and self-discipline have long been leveraged by innovative industries worldwide, yet the health care industry has been slow to catch up. Our CEOs are leading the way. Here’s why and how these qualities are so critical to their enhancing their leadership skills.

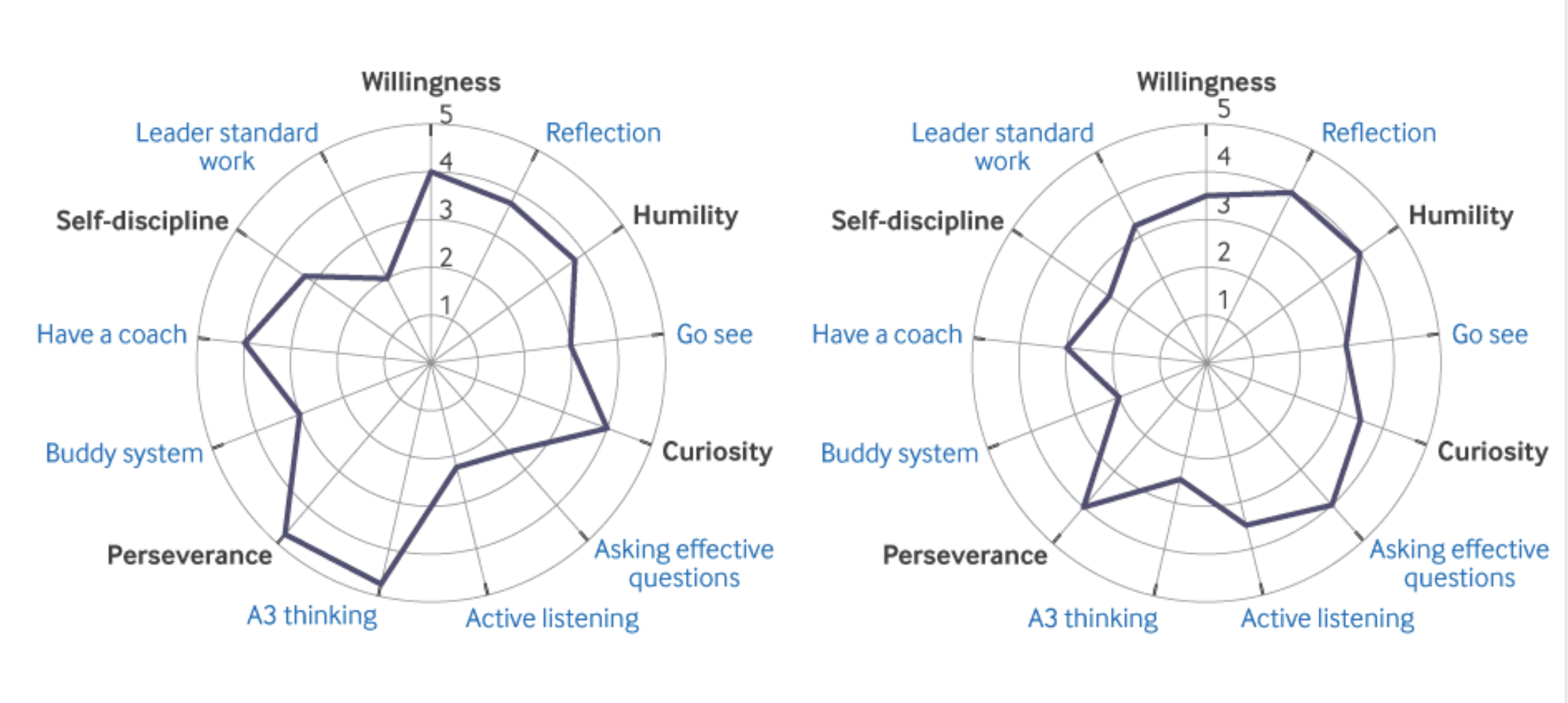

Render Charts Illustrating Five Behavioural Dimensions, with Associated Reinforcing Behavious (in blue)

Willingness

The key factor enabling personal change, and what drives the cultivation of the other behavioral dimensions, is first recognizing that change is required, which then leads to the willingness to do so. Leaders cannot address unproductive organizational traits (redirected blame, autocracy, etc.) without being open to extricating these traits from themselves. We as health care leaders must assume responsibility for poor patient outcomes, as well as staff and physician burnout — much in the way that good teachers can acknowledge how their lessons might not be reaching students. Positive transformation requires a state of readiness for making the personal changes that allow leaders to improve their interactions with others.

To facilitate willingness, we encourage leaders to commit to 10 minutes of self-reflection weekly, telling them to ask themselves, What in my actions this week led to better thinking on behalf of my team about problems? Did my questions unleash the thinking capacity of my team, or did I blame them for not following up on my specific ideas?

Humility

In a recent Journal of Management study of 105 small-to-medium companies, humility was the best determinant of process and outcome performance in comparative study. In a 2005 Harvard Business Reviewarticle, renowned business consultant Jim Collins identified personal humility as being the “yin” to the “yang” of will, and an indispensable characteristic for transforming a good company into a great one.

The key factor enabling personal change, and what drives the cultivation of the other behavioral dimensions, is first recognizing that change is required, which then leads to the willingness to do so.”

The capacity for humility is essential for leading complex teams, where participants are often more expert than leaders in a particular area. Effective leaders know they do not have all the answers and are willing to “go see” — to be present where the actual work is done — and to respect workers by asking open-ended questions and seeking input.

Many leaders have difficulty setting aside their preconceived ideas to learn from frontline doctors, nurses, and technicians who have firsthand experience in dealing with issues. Leaders should therefore proactively examine their interactions with others and ask themselves, Did I ask questions that elicited the best thinking of the person or team with whom I interacted? Were there implied answers in my questions?

Curiosity

When General Motors and Toyota embarked on the New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI) automobile plant in Fremont, California, in 1984, Japanese executives replaced the struggling US automakers’ original management with people hired based essentially on one characteristic: curiosity. They wanted people who were interested in how and why things worked and how to fix what was not working.

Effective leaders know they do not have all the answers and are willing to ‘go see’ — to be present where the actual work is done — and to respect workers by asking open-ended questions and seeking input.”

They also adopted a curiosity-driven problem-solving approach known as “A3 thinking.” A3 describes an 11 × 17-inch worksheet that workers use to tell a story, starting with the background and current state of a problem. The method calls for defining the problem, identifying a target condition for the issue, analyzing why the problem exists, and coming up with possible experiments to the root cause of the problem. Conceptually, it is similar to the SOAP note (Subjective-Objective-Assessment-Plan). Physicians are trained to use the scientific method to solve clinical problems and use the SOAP note to manage patients. A3 thinking is like a SOAP note applied to daily problems.

We believe in continuous learning and teach A3 thinking because it forces leaders to exercise their curiosity and think more deeply about a problem before considering a solution. Being curious also means being willing to “go see” and to ask oneself, Did I unleash the creativity of my team by asking them about how things work and how they should work? Did I see barriers I could remove that would allow them to solve the problems they face?

Perseverance

Perseverance is the persistence to attack any problem and the belief that no problem is unsolvable — what former SVP of Google’s People Operations, Lazlo Bock, calls grit. Collins calls it “ferocious resolve.”

Is there anything on my calendar this week that will add value to the patients we serve? Have I gone to where value is created to observe, show respect, and encourage the staff?”

Changing one’s behavior requires psychological resilience and the persistence to attack any personal problem. Learning a new skill requires two things: a teacher and practice. Learning to be a continuous improvement leader is no different. Having a coach who observes your daily interactions is invaluable. You must learn to go see, not go tell.

We teach leaders to not let bad days affect their resolve to improve the patient experience. They should reinforce their commitment to change the culture of their organizations by asking themselves, Did I ask someone to observe my behavior and give me feedback this week? Have I established a confidant with whom I can share my behavioral struggles?

Self-discipline

In his bestselling book on organizational improvement, Good to Great, Collins states that “Sustained great results depend upon building a culture full of self-disciplined people who take disciplined action . . .” Such a culture develops out of effective leader standards. Leaders who follow a system of management that sets expectations for everyone involved and reduces second-guessing regarding what others need allows for better-informed decision-making and problem-solving on the fly.

We encourage our CEOs to condition themselves to a habit of self-discipline in thought and action, and to routinely ask themselves, Is there anything on my calendar this week that will add value to the patients we serve? Have I gone to where value is created to observe, show respect, and encourage the staff?

Case Study

When leaders actively pursue and manifest all five behavioral dimensions, we have seen remarkable results occur. Since 2011, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center (ZSFGH) has been on a transformational journey to provide high-value, patient-centered care. Under the guidance of one of us, ZSFGH’s CEO Susan Ehrlich, the hospital has focused on implementing a handful of organizational metrics described as “True North” (equity, safety, quality, care experience, workforce care and development, and financial stewardship).

Efforts began with a pilot project in which a standard daily management system (DMS) developed by Catalysis was established for five “model cells”: perioperative services, an inpatient unit, an urgent care clinic, specialty clinics, and the emergency department (ED). The DMS would help engage staff in identifying and solving problems aligned with True North metrics. Training in A3 thinking was simultaneously initiated to teach leaders to identify, define, analyze, and develop plans to solve problems at the frontline level.

Institutional problems cannot be effectively managed ‘top down.’ The old way of autocratic action must cede to processes designed to build a continuous improvement culture.’

Adopting the DMS, as well as executing value stream mapping and improvement events throughout ZSFGH, led to additional measurable improvements, including shorter cycle times for lower-acuity patients in the ED, a greater capacity to see patients in the urgent care clinic, and reduced wait times for prescriptions in the outpatient pharmacy. However, the work also made the team realize that all leaders needed more education, support, and feedback so as to contribute meaningfully to the institution’s transformational journey.

In fall 2016, ZSFGH management implemented a second phase focused more deeply on developing leader behaviors that truly supported the principles of “align, enable, and improve” — areas that frame ZSFGH’s management of process. This included developing radar charts (see Figures 1 and 2) on the executive team to gauge leadership performance on behaviors aligned with institutional principles and then using the information to improve over time. For example, the characteristic of “humility” aligns with enabling people, whereas “A3 thinking” demonstrates an improvement mindset. Using radar charts also allowed the team to pilot 360 evaluations with one-ups, colleagues, and direct reports — thus facilitating Personal Development Plan (PDP) A3s — as well as to focus on optimizing leader standard work.

This work has recently been expanded from 14 to 53 of the highest-level organizational leaders, including medical staff leaders. The leaders themselves have enthusiastically embraced resources and feedback regarding their individual development, while an “esprit de corps” has infused the group overall. This team approach continues to pay dividends in hospital operations and delivery of the highest quality care to patients.

Conclusion

Institutional problems cannot be effectively managed “top down.” The old way of autocratic action must cede to processes designed to build a continuous improvement culture. To achieve a much-needed breakthrough in meaningful cost and quality care results, as well as to promote positive changes in staff members, a leader — whether executive, physician, or clinic leader — must be open to improving how he or she leads. By embracing the five behavioral dimensions of personal change we have outlined, leaders can inspire others and help build a culture that values — and seeks out — the contributions of an organization’s greatest asset: the people working at the front lines.

Acknowledgments: Karl Hoover from Karl Hoover & Associates, LLC, Seattle.

About the Author:

Health care delivery is undergoing a major transformation around quality, cost, and access. NEJM Catalyst brings health care executives, clinician leaders, and clinicians together to share innovative ideas and practical applications for enhancing the value of health care delivery.

Read The New England Journal of Medicine’s editorial: Leading the Transformation of Health Care Delivery — The Launch of NEJM Catalyst.